LOOKING BACK:

Tornadoes, ugly algae spurred community campaign that built a lab and the Freshwater Society

Posted January 20, 2010

By Dick Gray

It all started when a gang of five tornadoes passed across the Lake Minnetonka area, west of Minneapolis, on May 5, 1965. The violent winds and rains sped to the northeast, leveling dozens of houses, tearing trees to bits, destroying or severely damaging hundreds of boats and docks and flooding a huge swath of land normally dry. Unbelievable amounts of debris clogged the lake—houses, cars, belongings, dirt, vegetation, and even cows carried by the funnel clouds from farms near Norwood. Deep churning of the waters stirred up bottom sediment deposited over thousands of years. Contamination of all sorts threatened the healthy state of Lake Minnetonka.

The storms passed, but Lake Minnetonka and its 112 miles of shoreline were left a mess. Clean-up started immediately, but for weeks window frames, toy trumpets, clothing, checkbooks, and other components of life by the lake washed ashore.

Lake Minnetonka was suffering. The drastic disturbance to its sediments by the storm and clean-up over a large area altered the biota of the lake for months and even years. the lake was in a very unhealthy state. What to do?

In mid-1966, I enlisted the help of a friend, Hibbert Hill, to establish a small freshwater laboratory in the basement of my house on the western shore of Lake Minnetonka. Hib was vice president of engineering for Northern States Power Company and an avid water researcher. He had a similar small water laboratory in his house on Lotus Lake nearby. We established a plan. We lived on dissimilar bodies of water in the same neighborhood, and by comparing weekly water samples, we could track changes that occurred in the lakes.

Every Sunday morning at exactly 10 a.m. — rain or snow, cold or hot — we took our respective boats or walked on the ice to auger holes in the ice; sampled near-surface, mid-depths, and in the deeps; and delivered the samples to Hib’s house. We used our same set of instruments, clean and official every time, to test the samples. The lake locations of our sampling were duplicated each time via triangulation, on water or on ice. We discussed any changes that occurred in samples along with the probable reason or reasons for the changes.

One morning in February 1968, I bundled up and with my two golden retrievers I hauled my sled out onto the ice, triangulated my position, and started drilling through 20 inches of ice.

With ice chips flying, I made way into tho ice and broke through to water. The weight of the ice sheet forced water into and up the hole and out onto the ice surface—the ice and snow were suddenly stained a horrible red, and a very musty smell caused the dogs to growl…what the hell??

The dogs nosed the mess as I took a picture of them—a picture that became quite famous around the country and made the front page of the local Sun Newspaper. With extreme care, I took water samples at various depths, checked the oxygen level of each, and rushed indoors to my lab to observe under the microscope what the “red” was all about. I saw an astounding sight: a tangled mass of strand-like algae. The red color was later identified as that of Oscillatoria rubescens, a sure sign of bad pollution. I rushed the samples over to Hib Hill; he came back with me and we took further samples and both agreed we had a terrible problem on our hands and HAD to do something about it. We searched the literature and questioned scientists around the country—which took time but answered little.

In July 1968, I awoke one morning with the idea to solicit some knowledgeable person to answer the many lake problems that were popping up. I approached Hib Hill and Carroll Crawford of the Sun Newspapers about the idea and they supported it. Hib and I drove north to tho Biological Station of the University of Minnesota at Itasca State Park (at the head of the Mississippi River) to pass the idea by Dr. Alan Brook from England, new head of Ecology and Behavior Biology at the U of M who was teaching that summer at Itasca.

After several hours of discussion, during which Dr. Brook expressed his amazement there was no major freshwater research facility in the United States, the idea of establishing such a facility grew by the minute. During the drive back to Minneapolis. Hib and I further developed the idea, and the Freshwater Biological Institute was born. We decided the U of M was the prime candidate to be responsible for it.

The first move was for me to approach Dr. Malcolm Moos, president of the U of M. I called his office the next day, and two hours later I was sitting in his office on campus. He listened intently to me, made a few notes, and said I’d hear from the university soon. “Soon” was sooner than I had hoped. Three hours after I had left Dr. Moos, the dean of the College of Biological Sciences, Dr. Richard S. Caldecott, was sitting in my office, eager to hear the details of what we planned. From that day on, Dick Caldecott became an invaluable member of our Freshwater team, a member of our Board of Directors, and a close friend for 41 years.

The next major decision was to decide how to approach the many potential donors at all levels of the greater Twin Cities area regarding the proposed plans for a research facility. We decided to hold an informal master informational program at the Minikahda Club on Lake Calhoun in Minneapolis on a Sunday afternoon. We needed “a draw.” Arthur Godfrey of radio and TV fame was a prospect. Dick Caldecott and I made a cold call on Mr. Godfrey in his office in Now York City after an aviator friend of his broke the ice for us.

Mr. Godfrey was most gracious and agreed to fly to Minneapolis to address our party at the Minikahda Club some Sunday afternoon. The party was set for a Sunday in January 1969, and was attended by 250 people, a smash success.

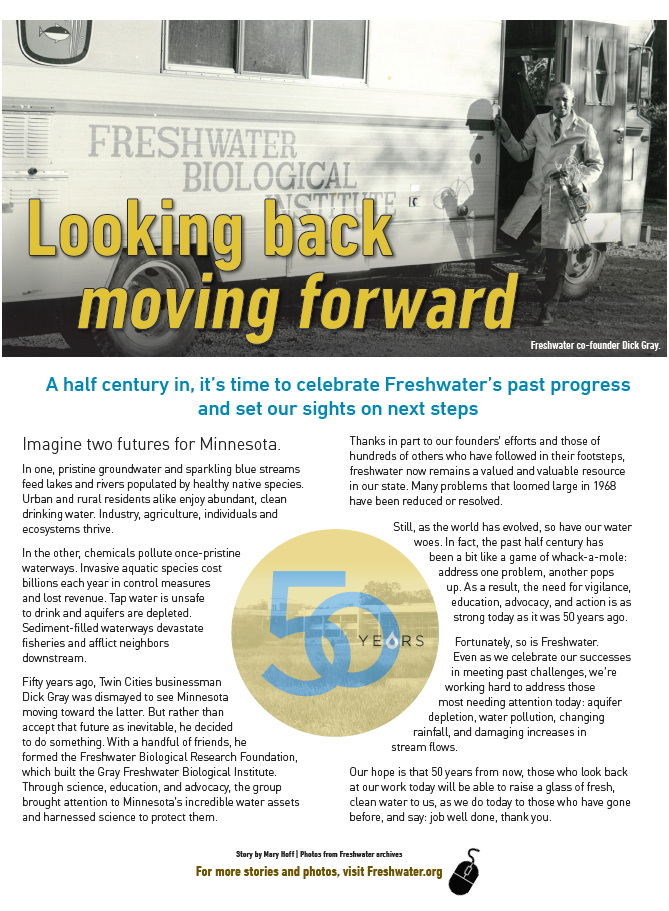

On Dec. 31, 1968, the non-profit “Freshwater Biological Research Foundation” was officially recognized by the State of Minnesota. A Board of Directors was formed (I was chairman) and an office was set up at my company, Zero-Max Industries in south Minneapolis. University personnel were most helpful in structuring a plan for the Freshwater Biological Institute, to be given, free and clear, to the university to own and operate on behalf of the people of the world.

The Freshwater Foundation moved its offices into the new 52,000 square-foot, multi-million-dollar Freshwater Biological Institute at Navarre on Lake Minnetonka in 1974. The multi-disciplinary laboratory for research and the training of doctoral students opened for business in June 1974, early and under budget.

On Dec. 9, 1976, the Freshwater Foundation officially gave the land, building, and equipment to the U of M with no strings attached. At a later date, the U of M renamed its facility the Gray Freshwater Biological Institute. Later, with the Freshwater Biological Institute up and running, it was decided the non-profit entity that organized the project should be renamed the Freshwater Society.

Special thanks must be given to lawyer-president Ray Black of Zero-Max Industries, without whom the Institute project would not have materialized. The Baker Foundation and Bill Baker of Minneapolis believed in the project from the start and supplied major seed money for architects and operations, and were instrumental in securing the gift of nearly 50 acres of precious land on Lake Minnetonka from IDS. Bill and his brother Roger were Freshwater Society board members for many years. Thanks also must be given to thousands of donors and helpers, mostly from the Twin Cities area. Theirs was a job well done.